The Nitrate Debate: Reducing Nitrogen Pollution Alone Won’t Stop Algae in Florida Springs, Researchers Say

The Nitrate Debate: Reducing Nitrogen Pollution Alone Won’t Stop Algae in Florida Springs, Researchers Say

By Patrick Farrar

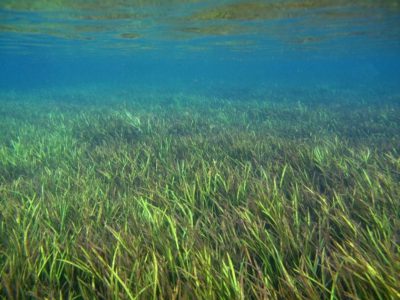

GAINESVILLE, Fla. – Visitors to popular Florida springs, particularly those along the Suwannee River, may notice something different about the plant life that coats the sandy bottoms. In some areas, the lush, flowing aquatic grass has been replaced by thick mats of algae.

These algal blooms are more than just an eyesore. In excess, they can crowd out plants like springtape and tapegrass that anchor the sediment below and provide habitat and food for crawfish, snails, small fish, turtles and manatees.

Nutrient pollution, particularly from excess nitrogen in the form of nitrate, is often considered by scientists to be a main culprit of these algal blooms. Seeping into our freshwater from aging wastewater systems and agricultural fields, nitrate provides fuel for algae to grow in places like estuaries. But researchers at the 2020 Water Institute Symposium, held in late February at the University of Florida, stated that the reality in the state’s springs is much more complicated.

“I think that one of the biggest misconceptions is that the reduction of nitrate is going to return our springs to their former glory,” said Gregory Owen, a senior planner with the Alachua County Environmental Protection Department. “For a long time, the framing of the issue has been oversimplified.”

Silver River (top) has nearly triple the nitrate concentration of Alexander Springs Creek. Photos courtesy Matt Cohen.

A growing body of research led by UF scientists suggests that for some springs, changes in water flow play a bigger role than nitrate levels in prompting the overgrowth of algae.

Increased water demand, heavy rainfall and changes to our landscape have been linked to a much higher frequency of springs experiencing flow reversals – that is, when murky river water flows into a spring instead of clear spring water feeding a river.

Flow reversals can reduce the amount of dissolved oxygen in the spring for weeks, potentially creating ecosystem-wide problems. Snails, for example, are important grazers that will snack on the algae, but less oxygen availability can harm their populations, helping algae take over. The dark water can also block sunlight, killing submerged plants and creating space for future algae accumulation.

Alexander Springs Creek is overrun with algae. Photos courtesy Matt Cohen

This knowledge led Matt Cohen, professor in the UF/IFAS School of Forest Resources and Conservation, to think differently about the way springs have been managed in the past, which was largely centered on reducing nitrogen pollution.

“The evidence for that nitrogen limitation story is actually not all that compelling,” Cohen said.

In his Feb. 25 symposium presentation, Cohen shared photos of springs with high nitrate concentrations and little algae growth alongside springs with lower nitrate concentrations and worrisome algae growth. Cohen explained that increasing a nutrient like nitrate should not play a big role in increased algae growth because the springs generally show many signs of nutrient saturation.

To explain nutrient saturation, “I like to make the analogy to Golden Corral,” Cohen said.

He describes the buffet: boasting much more food than a person could possibly eat. Adding more food to the buffet would not affect how much someone eats before becoming full. The same goes for algae in the springs: A smorgasbord of nutrients like nitrate flow through constantly, much more than they could possibly use. Adding more shouldn’t really affect their growth, Cohen said.

Changes in spring flow, he argued, must also help explain these massive algal accumulations.

But placing blame on nitrate is not without merit, said Robert Mattson, an environmental scientist at the St. Johns River Water Management District.

“There’s still a robust enough body of scientific evidence that indicates that [nitrate] is an issue in springs,” Mattson said. “Unfortunately, it’s not the silver bullet. Reducing nitrate won’t necessarily get rid of the algae, but it’s still something we’ve got to do.”

Cohen doesn’t disagree with Mattson; he just believes there’s more to the puzzle.

“We’re quite careful to say: Look, we don’t subscribe to the idea that we should do nothing. … We should better understand what to prioritize if springs restoration is our main goal,” Cohen said, adding that changes in spring flow must be included in restoration and policy decisions.

“If [agencies] are serious about remedying the springs,” Cohen said, “these linkages should be part of the conversation.”

Patrick Farrar is a senior Biology student at the University of Florida who is interested in communicating issues in ecology and environment. He departs for Senegal in September to serve in the Peace Corps Agroforestry sector.