Keeping Our Waters Safe: Researchers Test New Water Quality Technology

Keeping Our Waters Safe: Researchers Test New Water Quality Technology

By Felipe De La Guerra

GAINESVILLE, Fla. – A state famous for springs and beaches, Florida still seeks answers to its water problems: saltwater intrusion, pollution and harmful algal blooms are just a few.

Certain types of harmful algal blooms can cause respiratory and nervous system issues in humans, poison pets and lead beach and fisheries closures. For a state that generates $16.9 billion from the seafood industry, $82 billion from tourism and faces future freshwater shortages, that matters.

Better data could help scientists predict or prevent negative effects of poor water quality, such as algae blooms, but collecting these data can prove expensive, time consuming or even impossible.

Remote sensing is changing that. Drones, satellites and unmanned cameras collect what scientists call high resolution data. Just as a higher resolution photo is more detailed, high resolution data gives a clearer overall picture.

Remote sensing lets water quality experts see more than they could in person and process more data faster at a lower cost. Those experts discussed advancements in remote sensing at the 2020 Water Institute Symposium, which took place Feb. 25-25 at the University of Florida.

One advancement: using specialized cameras to observe how boat wakes impact the shore. Christine Angelini, associate professor of environmental engineering at UF, said researchers don’t know how many boats traverse Florida’s waterways or their cumulative effect on the environment.

“We have a pretty good idea of the amount of traffic that our roadways are handling,” Angelini said. “The equivalent of that on our waterways, we have no idea. It’s as if we just knew where the tractor trailers were going.”

Angelini’s lab ran solar-powered cameras continuously for three weeks. Rather than manually reviewing all that footage, the researchers used machine learning — a type of artificial intelligence — to analyze the type of craft passing. Coupling their videos with sensors in the water, they identified different vessel types and found that hull shape impacts the wake’s disturbance of the environment. Surprisingly, sailboats stir up the water more than some larger boats.

This pilot study was part of UF’s iCoast program, an initiative with the Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering and Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience to detect hazards to coastal areas, such as storm surge and flooding, saltwater intrusion and pathogens, and create forecasting models so communities can take steps to mitigate risk. But that is just one example of how scientists are using technology to advance the field.

Researchers use satellites to measure everything from soil moisture to concentration of atmospheric gases to sea level, according to David Kaplan, associate professor of environmental engineering and one of the leaders of the iCoast initiative.

Kaplan detailed how then-doctoral student Elliot White used satellites to monitor saltwater intrusion in coastal swamps. Analyzing upstream and downstream areas, scientists could observe effects and assess the swamp’s health. Satellites can also help researchers see things that aren’t noticeable to the naked eye.

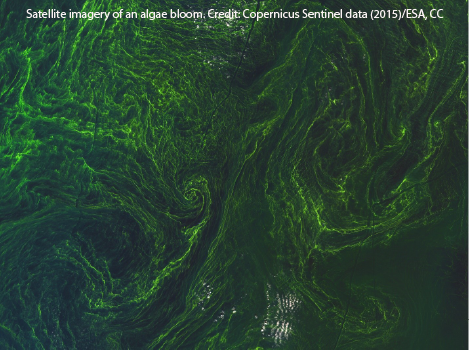

Satellite imagery of an algae bloom. Credit: Copernicus Sentinel data (2015)/ESA, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

A special type of imaging captures light beyond the visible spectrum. Organisms such as blue-green algae and red tide reflect particular wavelengths that can reveal concentrated areas. That data helps experts follow the movement of blooms, predict which areas will be affected and act to prevent negative effects.

Drones also played a prominent role in the symposium sessions. UF doctoral students Katie Glodzik and Gretchen Stokes used drone imagery to map water bodies and their vegetation for managing land such as stormwater treatment areas which play a crucial role in removing nutrient pollution from wastewater and agricultural runoff.

In another iCoast study, a team led by Peter Ifju, UF professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, flew specially built drones to collect water quality samples for analysis. Drones could gather more in a half hour flight than humans on a boat could in over an hour. While still in the pilot phase, the symposium demonstrations generate optimism in the field.

For Kaplan, this cheaper, faster alternative to manual sampling and surveying could be transformative.

“If you can do that job faster, then you can prevent people from getting sick earlier — from going on a polluted beach.”

But measuring and predicting is not enough. Remote sensing helps us better understand hazards and ways to solve them, but technology alone won’t stop them. Kaplan said stakeholders need to build consensus on how to fix these problems and take action.

“It’s like the canary in the coal mine. We’re doing a really good job measuring it but if you just keep losing canary after canary after canary, don’t pat yourself on the back.”

Felipe De La Guerra is a mass communications master’s student at UF and intern at the Thompson Earth Systems Institute. Through writing, video production and web development, he tells stories about food, culture, the environment and technology.